The Shape of Pasta HCII Assistant Professor Morphs Matter

Susie CribbsMonday, March 19, 2018Print this page.

Lining Yao came of age in a small village in China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Like most families in her town, she didn't have a computer. She didn't even have a television. On the eve of Chinese New Year, friends gathered at the only local home with a small black and white TV to watch China Central Television's New Year's Gala. When a car drove through her village — which happened only a few times a year — people would line the street and wave to welcome it. Her family grew most of their own food, and foraged for mushrooms in the forest.

Today, Yao directs the Morphing Matter Lab in Carnegie Mellon University's Human-Computer Interaction Institute, where she studies how to design and fabricate materials that use nano- and microscale technologies to alter their own shape. Examples? Clothing that self-ventilates in response to human sweat. Furniture that arrives in a flat package and self-assembles when exposed to a stimulus like heat or water. Flat pasta that takes its characteristic shape when boiled.

It might seem like a giant leap from Inner Mongolia to Pittsburgh, but Yao made a few stops along the way. The first was Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, where she enrolled in medical school. After two years, she realized she was better suited to a profession that allowed for more expression and exploration.

"I learned that I prefer creativity over reciting knowledge written in medical books," she said. "As a person who deals with creative technologies and exploration, you can be highly productive even if you are young and inexperienced, as long as you are passionate."

That passion propelled her to a bachelor's degree in engineering and industrial design in China, and then to MIT Media Lab, where she earned her master's and Ph.D. in media arts and science. This past June, she joined the HCII, whose advertisement for a "radical designer" who could also do research caught her attention in a big way. Because "radical" might be the best adjective to describe Yao's work.

Take, for example, the aforementioned flat pasta. Begun while she was finishing her Ph.D. in Media Lab with colleagues Wen Wang, Chin-Yi Cheng and Professor Hiroshi Ishii, the "Transformative Appetite" project generates 2-D films from food materials (protein, cellulose or starch) that transform into 3-D shapes when they're boiled. At the cellular level, the film material is designed to swell when it encounters water, but also contains molecular elements that help limit and control the swelling, resulting in the desired "pasta" shape. While early prototypes used gelatin as a primary base, Yao has reached out to Barilla since arriving at CMU and formed a partnership to create a substance that tastes more like real pasta.

"They're shipping us their semolina flour all the way from Italy," Yao said, "and they've been giving us a lot of insight into flour science in general. We're very keen to work out something that's actually authentic."

The motivation for the flat-pasta project is two-fold. First, she hopes to prove that something as universal as an object's water absorption behavior can not only be controlled, but can also be programmed. Beyond the scientific merit of the work, though, is the impact it could have on the world. Shipping flat pasta drastically reduces costs and eliminates unnecessary packaging. In fact, Yao says her team calculated that shipping flat pasta would save nearly 60 percent of packaging costs compared to today's traditional pasta.

Yao's work doesn't stop at food, though. She's also tackling adaptive garments.

"By adaptive, I mean that all of the physical materials should understand the environment and the user, and be responsive and accommodating in a way that's more beneficial to its host and the ecosystem," Yao said.

Through CMU's Center for Machine Learning and Health, she hopes to join forces with UPMC to develop fabric that responds to a patient's fluctuations in perspiration and temperature using thermo- or water-responsive polymers. Students from her lab — which includes disciplines ranging from materials science and engineering and mechanical engineering to computer science and costume design — even developed clothing that responded to heat for CMU's Lunar Gala fashion show, held earlier this month. This work could pave the way for sleeves that roll themselves up or jackets that puff up when temperatures drop.

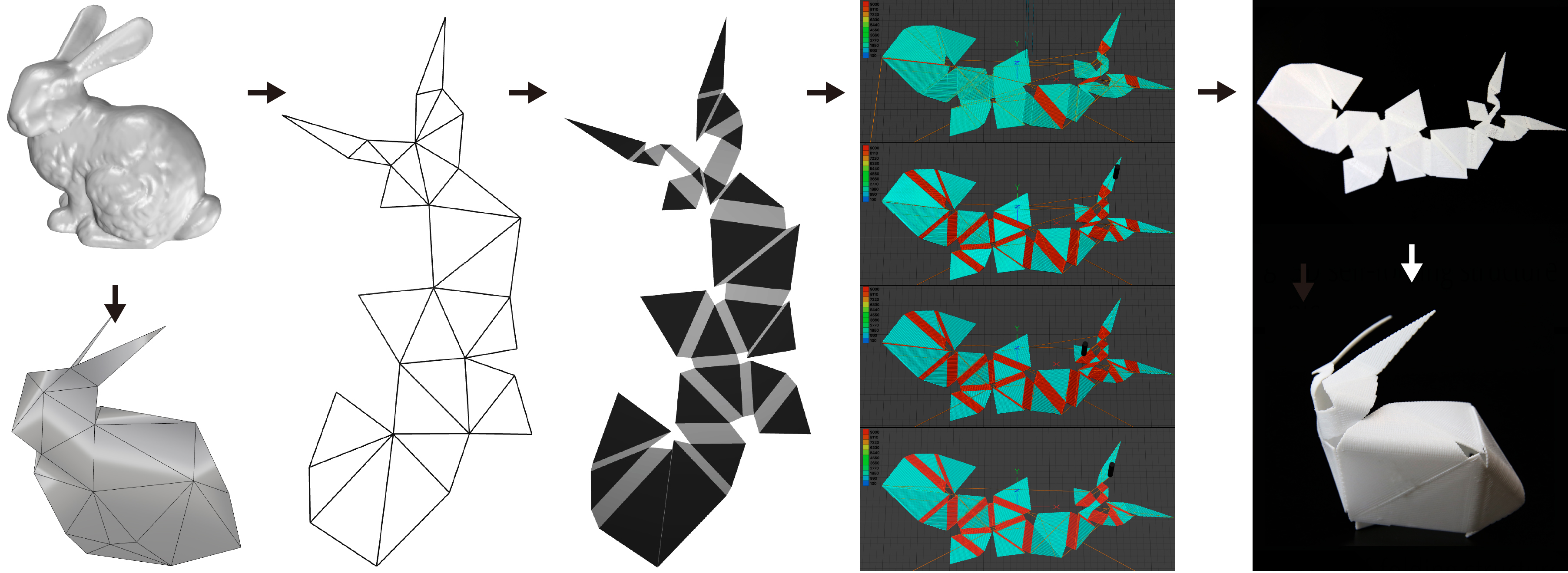

While it might seem as though Yao's work has a strong design focus, the computer science aspects of it can't be denied. All of her work — the pasta, clothing, furniture and beyond – relies on 3-D printing and fabrication, which in turn relies on intense computation and graphic models that allow you to input the 3-D item and transform it into printable 2-D coordinates.

Yao says that the HCII is a perfect fit for her lab because the institute allows her to explore her creativity in an interdisciplinary environment that prizes collaboration.

"One valuable element at Carnegie Mellon is that all the professors from different departments are really open to collaboration, and people think together we can make the world better," she said. "That's what they told me before I took the offer, and it's what I've experienced since I arrived on campus." Two examples of this kind of collaboration include her works with CMU’s Manufacturing Futures Initiative and NextManufacturing Center.

If all this seems a world away from her Inner Mongolian roots, she'd be the first to tell you you're wrong. Her technology-free, nature-heavy childhood informs nearly all she does.

"Inner Mongolia is full of grass, but also forest and mountains, especially pine trees. We used to pick mushrooms and pine cones," she said. "These all became part of the natural organisms I studied for inspiration on how nature's smart materials work."

Pine cones, she points out, have scales that close when wet, but open when they're dry — a reversible transformation from one of nature's smart materials that had a huge influence on her research agenda.

"Nowadays, when I share my story with friends, I always talk about my home with pride. The pine cone is only an example. In general, the Morphing Matters Lab is a bio-inspired group — plants and microorganism-inspired mechanisms are critical to what I do now. When we study a new thing, I can almost always retrieve a childhood memory from nature related to it. I think that's why I'm so motivated to study all these things."

Headline help from Bryan Burtner.

Byron Spice | 412-268-9068 | bspice@cs.cmu.edu