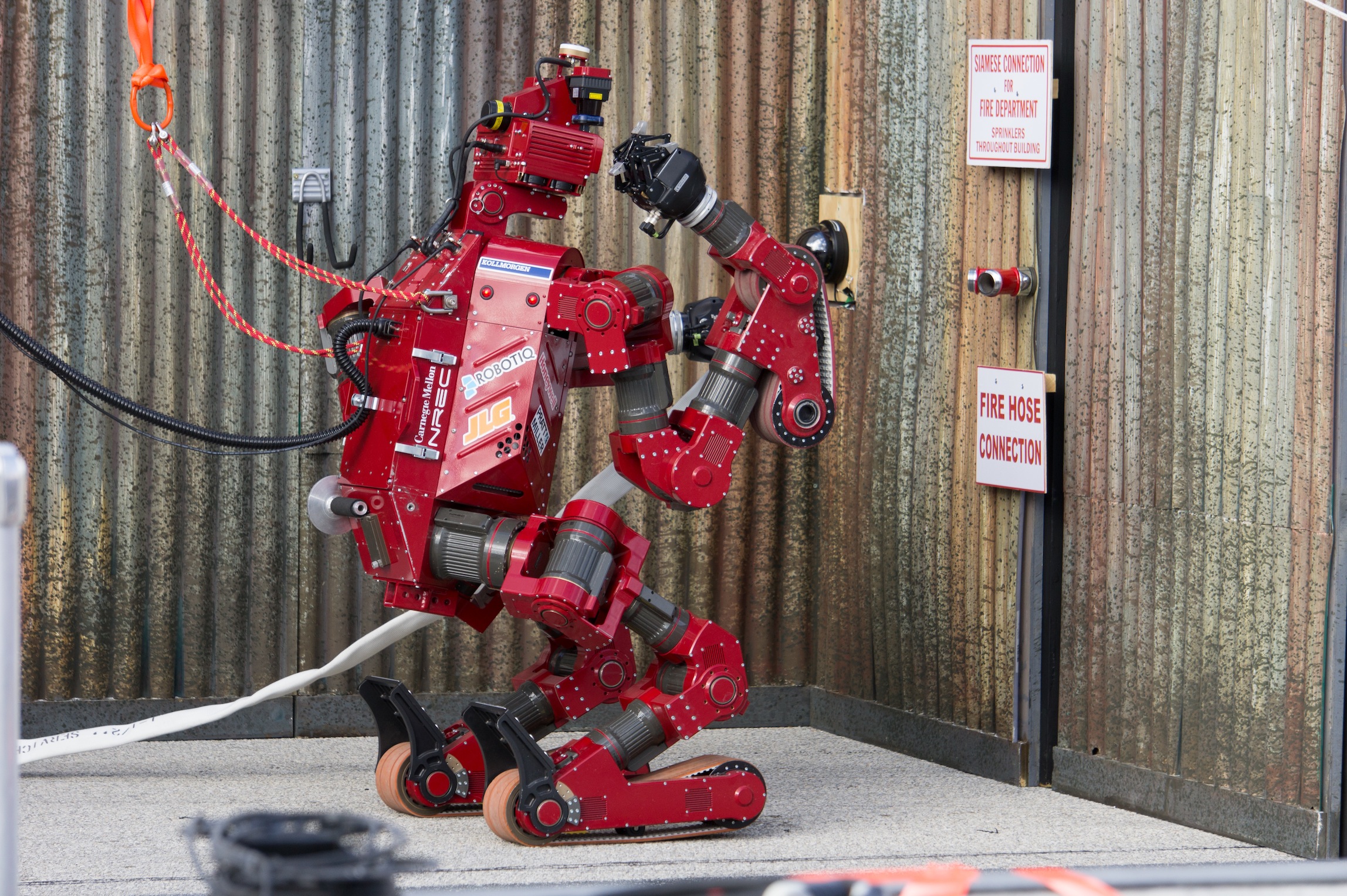

Photo courtesy DARPA.

The task appears simple. Walk through three doors. That means grasping the handle, turning it, and pulling or pushing the door before passing through it.

Most of us do that every day, without much thought. But for CHIMP—the CMU Highly Intelligent Mobile Platform—this requires a lot of practice.

Its “eyes” must look at the door and send video back to a human operator who’s controlling CHIMP from a trailer. From the grainy 3D images, the operator must assess the situation and tell CHIMP what to do. Is it a doorknob or a door lever? How should CHIMP grasp it? Does the door push out or swing in?

CHIMP was created at Carnegie Mellon’s National Robotics Engineering Center. It exists—in part—because of the Fukushima nuclear plant disaster. On March 11, 2011, a tsunami struck the east coast of Japan’s most populous island, Honshu, damaging the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant and eventually leading to a meltdown of three out of six nuclear reactors. With radiation at alarming levels, it remains impossible for human workers to enter much of the facility. Several robots have entered the plant to gather information and data, but some of those robots failed mid-mission and were abandoned.

In 2012, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Project Agency created the DARPA Robotics Challenge. Teams were challenged to create semi-autonomous robots that could do “complex tasks in dangerous, degraded, human-engineered environments.” The tasks include driving a vehicle intended for humans, navigating terrain, climbing a ladder, moving debris from a doorway and walking through it, opening and passing through doors, cutting a triangle out of a wall, closing a valve and attaching a hose.

During trials held in Homestead, Fla., in December 2013, CHIMP navigated a human-sized environment with ease, earning enough points to move into the final round of competition, scheduled for later this year. One of 11 robots headed to the final round, CHIMP placed third in the trials, ahead of some formidable opponents, including robots from Johnson Space Center and MIT. (Tartan Rescue wasn’t the only CMU-related team to reach the finals. A team fielded by Worcester Polytechnic Institute, which includes CMU roboticist Christopher Atkeson and six CMU grad students or post-docs, finished seventh in the same competition. See sidebar.)

CHIMP certainly shares some characteristics with its namesake animal. It has two long arms and a strong back. The red robot also looks vaguely human. It stands on two legs, but instead of feet, it rolls on tracks like those of a tank; it also has tracks on its forearms, so it can bend down and drive around like an all-terrain vehicle. Cameras perched on its squat, square head give the robot two sets of eyes for 3D imaging.

“The advantage of a humanoid robot, given its human form, is that it can fit into human spaces and do things humans do,” says Tony Stentz, NREC director and leader of Tartan Rescue.

A robot that can stand on two legs and maneuver in spaces where humans normally work could help clean up nuclear disasters or shimmy into tight spaces in mines and factories. But many of the existing bipedal robots aren’t advanced enough to perform human tasks like opening doors or turning valves, which is why DARPA introduced the challenge. The competition pushed teams to develop a robot quickly. “It was a very ambitious goal, but not impossible,” Stentz says. “We like challenges. They’re fun, and they motivate the team to work hard.”

In October 2012, CHIMP existed only as a concept on a piece of paper; NREC didn’t have a humanoid robot under development. And it was what NREC didn’t have that made the contest so important, says Herman Herman, principal NREC commercialization specialist.

“In order to be relevant, we needed to design a humanoid robot,” says Herman, who serves as sensor pod and electronics lead for CHIMP.

Teams in the Robotics Challenge could enter in one of four tracks. In track A, teams whose proposals were accepted received $3 million to both build a robot and design its software. In track B, teams received $1 million and developed software only for the existing Atlas robot, made by Boston Dynamics. “On the plus side, you don’t have to build you own robot,” Herman says. “On the minus side, you have to live with (the robot’s) shortcomings.” (Tracks C and D received no DARPA funding. The WPI-CMU team competed in Track B.)

Because Tartan Rescue was designing and building a robot from scratch, and was on an accelerated schedule, the team had to make some tough choices. Many of the decisions were constrained by time and money.

“I just say ‘no’ a lot,” says David Stager, the systems engineering lead and senior NREC commercialization specialist. He’s joking, and adds that all of the decisions were made after careful deliberation: “I’ve been trying not to close out really good ideas.”

To earn all 32 points in the Homestead trials, a robot needed to finish each of eight assigned tasks in 30 minutes. The first thing the Tartan Rescue team had to decide was whether CHIMP would compete in all the tasks. Stager and Clark Haynes, CHIMP’s software lead and senior robotics engineer, balanced the value of the points against the amount of effort it would take to develop the necessary software. They decided that CHIMP would compete in only enough tasks to win 20 points.

It was a risk. Could CHIMP be competitive if its design didn’t allow for all 32 points? But the team wanted to design a robot that played to NREC’s strengths: Engineering and building solid yet sophisticated industrial robots and field vehicles. Although a humanoid robot, CHIMP’s design is informed by NREC’s experience making other, non-humanoid robots, Herman says.

At 5-feet-tall, CHIMP is squat, but it has a powerful build, weighing in at 400 pounds. That makes it the heaviest robot in the competition. Being such a big robot provided CHIMP with an advantage—it was the only robot in the trials that didn’t stumble and fall. During testing, CHIMP was commanded to move a two-by-four piece of lumber. Due to operator errors, CHIMP used its gripper to drive the wood right into a concrete-block wall. The robot didn’t budge. And it didn’t drop the lumber. “The wall fell over—but CHIMP didn’t move,” Haynes says.

Being a brute of a bot poses other challenges as well. “As you try to make a robot more capable, it gets heavier,” Stentz says. “Our biggest concern is that CHIMP has to drive a vehicle. That’s where a bigger, bulker robot has a disadvantage.” Driving a vehicle was one task left out of CHIMP’s initial design; the team decided it would be too difficult to design and program a robot for driving in the short amount of time available.

“We knew what points we could get,” Stager says. “This year (2013) was about getting to be one of the top teams.”

CHIMP also didn’t get all the points for the ladder challenge. It earned one point for stepping onto the ladder, but it wasn’t designed to climb it.

The two teams that earned first and second, Schaft Inc. and IHMC Robotics, both worked with existing robots; Schaft, a Japanese startup company recently acquired by Google, used its own HRP-2 robot, while IHMC used the Atlas robot. Considering CHIMP was little over a year old, it did remarkably well. “I actually think that CHIMP is one of the best-designed robots in the competition,” Stager says.

But the team now faces another challenge—improving CHIMP to compete in all the tasks. The eight top teams won $1 million to upgrade their robots for the final competition. While the Tartan Rescue team is glad to have the money, Stager estimates they need about $5 million to $6 million to get CHIMP into competition shape. “This technology is really expensive to develop,” he says.

If the team attracts additional money, it will thoroughly upgrade CHIMP for the finals. If it doesn’t, it will improve the software and make sure the same robot can compete in all eight tasks.

Although the tasks in the finals are expected to be similar to those in the December 2013 trials, the team expects they’ll have an added level of difficulty. All of the robots in the trials were tethered to off-board power supplies, and Stentz suspects DARPA will require the robots to compete without tethers. As of this writing, DARPA has not yet released all of the details of the final competition.

“It’s a one-of-a-kind competition,” Herman says. “We will go up against some big competitors.”

Pittsburgh-based freelance writer Meghan Holohan is a regular contributor to The Link whose stories also appear at the Mental Floss and MSNBC Web sites. | thelink@cs.cmu.edu